Promoters : Aurora Francois (UCL-LaRHis), Xavier Rousseaux (UCL-CHDJ), Nathalie Tousignant (USL-B – CRHiDI)

PhD students : Amandine Dumont (UCL) and Pascaline Le Polain (USL-B)

Steering committee: Anne Cornet (MRAC), Aurora Francois (UCL-LaRHis), Francoise Muller (UCL-CHDJ), Enika Ngongo (USL-B – CRHiDI), Berengere Piret (USL-B – CRHiDI), Pierre-Luc Plasman (UCL), Xavier Rousseaux (UCL-CHDJ), Nathalie Tousignant (USL-B – CRHiDI), Patricia Van Schuylenbergh (MRAC)

Funding: FRNS

Duration: 01/07/2014-30/06/2018

Go directly to:

1. Research objectives

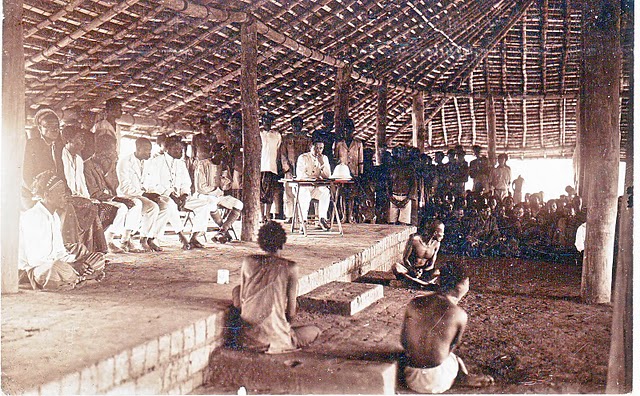

The project aims to study the collective profile of the judiciary of the Congo Free State (EIC), from Belgium and Rwanda-Urundi de 1885, date of foundation of the EIC, to 1962, date of the end of the mandatory regime in Ruanda-Urundi. By “judiciary”, we mean on the one hand the personnel empowered to dispense justice (judges, prosecutors, territorial administrators) (env. 1700 people), and on the other hand the institutional structures (courts and tribunals) on which is articulated the exercise of justice in the colonial space.

The objective is to go beyond the creation of a biographical directory or a dictionary to carry out a real prosopography of the “African” magistrates of 1885 to 1908 and of 1908 to 1962, based on network analysis. By combining the expertise of the three co-promoters, the project tests the innovation potential produced by the prosopographic tool applied to a delimited corpus (the Belgian colonial environment between 1885 and 1962) whose many interconnections we sense. This analysis will make it possible to support many hypotheses formulated around the constitution of the “colonial sciences”.’ in Belgium1 and intellectual networks active in legal journals((VANDENBOGAERDE S., « Exegi Monumentum : La Belgique judiciaire (1842-1939) », in Tijdschrift voor Tijdschriftstudies, 31, 2012, p. 41-58.)). From clues gleaned from the archives, the project will build a systematic analysis of the paths and intellectual filiations, socio-economic strategies and convergent interests of the three pillars of the colonial world.

Since 2011, priority was given to the study of the installation of this justice and its first magistrates, during the IEC period (1885-1908). It is now a matter of completing the following phases : Belgian Congo (1908-1960) and Ruanda-Urundi (1923-1962) to cover jurisdictions and public data until the end of the colonial era. Previous work has suggested the limited budget resources available to the administration of the colony and the mandated territories.((VANTHEMSCHE G., La Belgique et le Congo (1885-1980), Brussels, Le Cri, 2010.

PLASMAN P. -L., « Le pouvoir judiciaire au sein du Congo léopoldien. Entre faire-valoir et élément perturbateurs », in BRAILLON C., MONTEL L., PIRET B. and PLASMAN P.-L. (éds.), Droit et justice coloniale en Afrique. Traditions, productions, réformes, Brussels, Cahiers du CRHIDI, vol. 37, 2013.)). If the bulk of the budget is devoted to the Force Publique, the establishment of a judicial system is based on the joint action of the territorial administration and a colonial judiciary((PIRET B., « Les structures judiciaires du Congo belge. Le cas du tribunal de district (1930-1960) », in BRAILLON C., MONTEL L., PIRET B. and PLASMAN P.-L. (éds.), Droit et justice coloniale en Afrique. Traditions, productions, réformes, Brussels, Cahiers du CRHIDI, vol. 37, 2013.)). With limited human resources transferred on a three-year basis, the networks are set up by the daily activity of these magistrates. Hence the interest of exhuming these multiple links that are woven over the years spent in Congo and Ruanda-Urundi.. For years 1910-1962, the career files of the magistrates exist and their consultation can be the subject of an exemption. The data from this collection will be directly integrated into the database "prosopography and directory of the Belgian judiciary".((MULLER F., « Prosopographie et répertoire de la magistrature belge (1830-1914). De l’utilité des bases de données », in Clio, revue de l’Association des historiens et du Département d’histoire de l’UCL, n°126, 2007, p. 18-19.)), so that they can be analyzed from a prosopographic perspective, including a reticular dimension and a trajectory approach.

In the very dynamic field of colonial studies, the more general question of development of colonial law and specific justice, plays a fundamental role. Indeed, the implementation of the law and the control of its application by the police and by the justice denotes the political power of a State to take control of the territory and the people, to square this territory and to exercise the forms of regulation there to maintain its domination. But through the study of the group of jurists, it is not only about relations of domination. The coexistence of different legal traditions, and the invention of colonial law are concomitant with the rise of maritime law, commercial or international and the globalization of legal culture, which raises the question of the ability of jurists to shape a state through “law” at the dawn of the 20th century. The question is all the more important for Belgium, that its colonial role is regularly highlighted negatively in international literature (ex.: the “red rubber” scandal, the assassination of Patrice Lumumba). Belgian colonization is often presented as a paternalistic "model", animated by violent and stubborn expatriates, dominated by missionary rivalries and devoid of societal vision. This criticism is rooted in particular in the controversy over the mistreatment of the natives under the EIC and during the world wars.. Since then, to contextualize the work of the legal apparatus and personnel, it is important to connect these denunciations to the existence of a specific colonial project, which would differ depending on whether it is the Leopoldian EIC or the Belgian Congo.

Studying the judiciary proves to be a good observatory of practices, or even the existence of possible successive patterns of colonization. Analyzing them from the angle of collective biographies is a way of confirming, to invalidate or qualify the existence of a “Belgian colonial state model”, often confused with the personal project of King Leopold II.

2. State of the art

Little research has been devoted to the establishment of the legal apparatus and the personnel associated with it in the African territories under the trusteeship of Belgium. 1885 to 1962. At this level, research on small powers, including Belgium, looks like a poor relation compared to the booming one relating to the colonial administrations of the great European powers (British Empire((SEMAKULA KIWANUKA M., «Colonial policies and administrations in Africa: the Myths of the contrasts», in African Historical Studies, 3-2, 1970, p. 295-315.)), France((FABRE M., « Le magistrat Outre-mer, un élément capital de la stratégie coloniale », in La Justice et le droit instruments d’une stratégie coloniale, Rapport fait à la mission de Recherche Droit et Justice, 2001 ; FABRE M., « Les justices coloniales : clones imparfaits du système judiciaire métropolitain », in Quaderni Fiorentini, 2005, n° 33/34, t. II, Milan, 2005.

DURANT B., « Le Parquet et la Brousse. Procureurs généraux et Ministère public dans les colonies françaises sous la Troisième République », in Staatsanwaltschaft, Europaische und amerikanische Geschichten, Frankfurt am Main, Max-Planch-Institut, Klosterman, 2005, p. 105-137.

RENUCCI F. (éd.), Dictionnaire des juristes ultramarins (16e-20e siècles), December 2012.

FARCY J-Cl., « Quelques données statistiques sur la magistrature coloniale française (1837-1987) », in Clio&Themis, n°4, march 2011.)). This theme is also part of the dynamic research on the role of law in the “process” of westernization of the world ((BENTON L., Law and colonial cultures: legal regimes in world history, 1400-1900, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2002 ; BENTON L., A search for sovereignty: law and geography in European Empires, 1400-1900, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2010.

KOSKENNIEMI M., The gentle civilizer of nations: the rise and fall of international law, 1870-1960, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2002.)). The results are therefore intended to fit in an innovative way with the current of research on the construction of the Western colonial order in resonance with the construction of the national state and the central role of justice and administration in this process.((YOUNG C., The African colonial State in comparative perspective, New Haven, Yale University Press, 1994.)).

3. Research project

To meet the research objectives, several hypotheses must be formulated and verified.

The first hypothesis is that on the long term (1885-1960), the colonial system, if it exists, was built by a triple acculturation((ROUSSEAUX X., LÉVY R. (éds.), Le pénal dans tous ses états. Justice, Etats et sociétés en Europe (12e-20e siècles), Brussels, Publications des FUSL, 1997.)):

- The creation of the EIC corresponds first to a stage of formation of a more or less homogeneous body, from original individuals, of education and diversified and dispersed projects over an immense territory. Many magistrates come from “small countries” excluded from the colonization race or from nations lagging behind in national unity. As such, the period is comparable to the process of formation of the Belgian judiciary during the annexation to the French Republic and Empire (1795-1814)((LOGIE J., Les magistrats des cours et des tribunaux en Belgique (1794-1814). Essai d’approche politique et sociale, Geneva, Droz, 1998.)).

- At a second level, the acculturation of colonial justice to Belgian justice is a process that has been more particularly highlighted since the Colonial Charter (1908) until the interwar period. La justice se « belgicise », as shown by the evolution of the Superior Council of Congo, created in 1889 by the Leopoldian administration then abolished in 1930, with the extension to the Congo of the jurisdiction of the Belgian Court of Cassation from 1924((HAYOIT DE TERMICOURT R., Le Conseil supérieur du Congo 1889-1930: discours prononcé par M. Hayoit de Termicourt, à l’audience solennelle de rentrée du 1e septembre 1960, Brussels, E. Bruylant, 1960, p. 501-504.)).

- A third level, rarely studied, concerns the acculturation of Belgian law to African society. Manifesto from the reforms of the years 1920, through the integration of indigenous courts into the hierarchy of colonial jurisdictions, this aspect is less well known because of the failure of the reforms after the Second World War, and the speed of the transition, in 1960. Influences of colonial law on Belgian law, individual mobility from the colony to the metropolis, integration of colonial law in the training of jurists, so many places of observation of this “Africanization of judicial Belgium” still unknown.

At these three levels, the study of the determinants of the social group formed by the magistrates in the service of the colonial state should make it possible to identify the coherence of the practices of colonial governance through the exercise of law and justice.

The second hypothesis formulated is that the judiciary, or at least part of it – for example its members from, sous l’EIC, humanist networks – could play a moderating role, in the exercise of often arbitrary coercive power, when it emanated in particular from military or administrative authorities. The first grid of the territory of the EIC is in fact essentially the fact of the military, then administrators. The first judicial authorities would gradually impose themselves, once the pacification zones have been returned to the civil administration. In this precise case, it would be necessary to carefully analyze those who, in Brussels, shaped colonial legal thought, especially from 1895, second generation of colonial jurists who distanced themselves from the servants of Leopold II and those who, in the field, in Boma or in the sectors to be taken over, manage daily life with financial constraints, budgetary and communication methods of the second half of the 19th century. Bringing to light the socio-professional profile of these men is essential to understand, within the colonial administration, interactions between court personnel, the administration and the army.

How does this staff, in particular by legal publications, does it contribute to the formation of a “Congolese” law from the EIC and does it legitimize itself as a civilizing agent through legal thought ? How did the "belgification" of the colony from 1908 does it link Congolese law to Belgian law, as shown by the example of the creation of the courts of appeal of Boma/Léopoldville and Élisabethville or the extension of the jurisdiction of the court of cassation to decisions of colonial courts and tribunals ? How does colonial law become autonomous vis-à-vis metropolitan law?, in particular in frontline justice or through the creation of indigenous jurisdictions ? What are the phases of the reforms of the colonial administration and what areas do they relate to? ? How do magistrates experience the weakening of the link with the metropolis in 1914-18, said rupture one 1940-44 and the crisis of 1959-60 ? Finally, how will the colonial apparatus inspire the organization of the SDN mandate on Ruanda-Urundi, since these latter territories are attached within the limits of the mandate, to the Congolese colonial system ?

Check these assumptions, in terms of professional trajectories building a state apparatus, involves answering many questions. Who are the men who leave for terms of two or three years ? What is their training, their place of origin (urban, rural), their political ground ? How old are they ? What are their motivations for leaving Africa? ? What professional trajectories do they follow ? What are their family ties ? The hypothesis of the gradual development of an entry channel through the colonial route into the legal environment (bar or even judiciary) metropolitan, thus contributing to exchanges in the direction colony-metropolis is verified ? What were the consequences of the two occupations of Belgium for the colonial judicial personnel? ? From the inter-war period and especially after 1945, when the "white" population of the colony becomes "belgicized" and settles in the long term with the arrival of women and children, Are we witnessing the creation of an “Africanized” administration ("black feet") or does the small number of colonials maintain a rigid and authoritarian system controlled from Brussels? Finally, what will become of these lawyers during independence? ? So many questions assuming knowledge of the composition of administrative staff with judgment skills on the territory of Central Africa.

Responding to it has become possible throughaccess and processing of the registers and files of the Africa Personnel Service (SPA), preserved in the Archives of Foreign Affairs in addition to many under-exploited printed sources (Official bulletins (BO), Directories, collections of circulars…). The study of the Congo Free State period (1885-1908) is based on the SPA registers which continue until 1913, supplemented by the BOs of the EIC (1885-1908). Magistrates active in the Congo during the years 1920 can be understood by examining Belgian Congo Yearbook. Those staying in Ruanda-Urundi between 1924 and 1962 are informed by the Official bulletin of Rwanda-Urundi. The jurists who left for the Belgian Congo in the era between 1930 and 1960 are included in the Bulletin officiel du Congo belge. This list can be supplemented by reading registers kept by the colonial administration such as the Register of judicial personnel on leave (1947-1952). The personal files of magistrates kept at the Library and Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (environ 600) are subject to derogation : the service, despite its small staff, has agreed to provide access to the career files of magistrates and to analyze, on demand, the files that might seem most relevant, for further qualitative research. This bundle of questions and the exploitation of sources will be tied together around a methodology : social network analysis (SNA). Indeed, the personnel of the colonial judiciary lends itself particularly well to a study of the networks, which requires a fairly clear delimitation of the social group studied, sometimes holding the "small world"((BIDART C., « Étudier les réseaux – Apports et perspectives pour les sciences sociales », in Informations sociales, 2008/3, n° 147, p. 34-45.)). The relational database "prosopography and directory of the Belgian judiciary" makes it possible to generate a map of individuals and the links they weave between them, these links being both characterized in their nature (family, friendly, professional, etc.) and recorded in time. Combined with a qualitative analysis dedicated to the investment of actors in the link, the maps produced on the basis of historical sources – although necessarily incomplete – generate illuminating arrangements((LEMERCIER C. « Analyse de réseaux et histoire », in Revue d’histoire moderne et contemporaine, 2/2005, n°52-2, p. 88-112.)).

An analysis of the socialization of colonial magistrates, posed in terms of concentration/dispersion, homogeneity/heterogeneity, interconnection/independence, symmetries/dysmetries, is likely to shed light on their constitution as a social body, and in many ways : methods of integration, permeability of different groups (Metropolis-Colony, Is West), weight of the structure and of the interactions on the modes of behavior((DEGENNE A., FORSE M., Les réseaux sociaux, Paris, Armand Colin, coll. « U », 2th edition, 2004.)). This approach will be coupled with an analysis of trajectories according to the optimal matching method “optimal Matching Analysis”((ABBOTT A., TSAY A., « Sequence Analysis and Optimal Matching Methods in Sociology », in Sociological Methods and Research, 2000, vol. 29, n°1, p. 3-33.)), in order to identify career logic based on multiple criteria.

- PONCELET M., L’invention des sciences coloniales belges, Paris, Karthala, 2008. [↩]