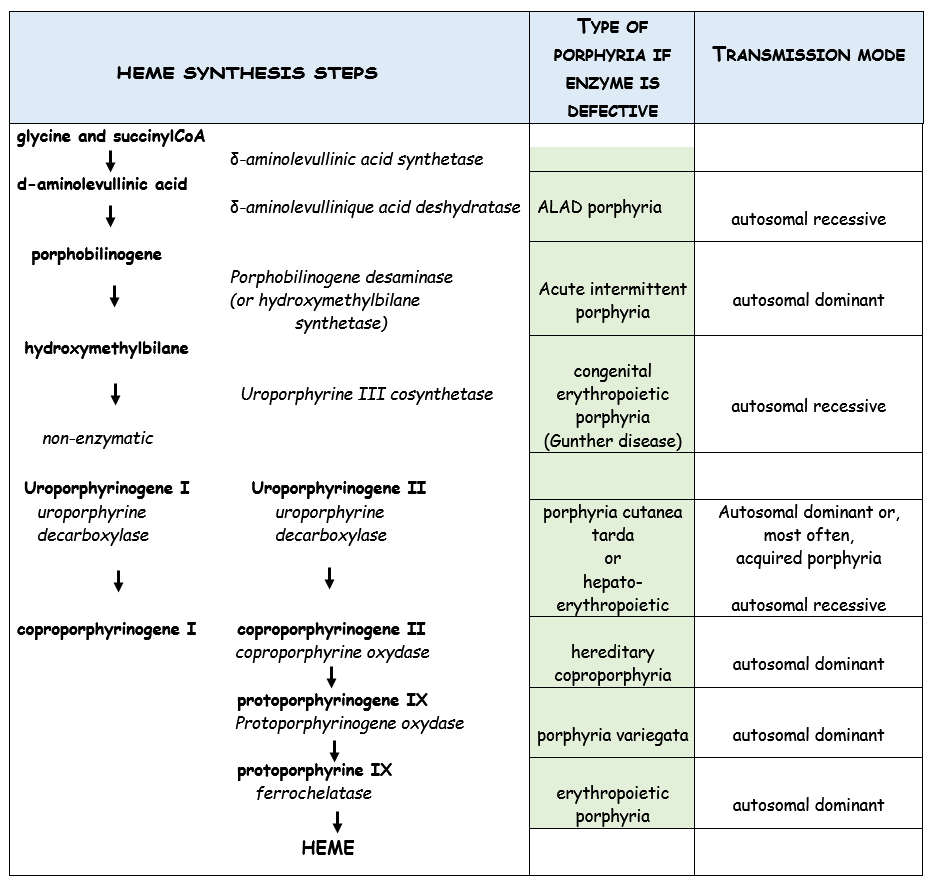

Heterogeneous group of 8 genetically transmitted diseases of the chain of synthesis of heme (see table), an essential component of hemoglobin. In France, acute intermittent porphyria is the most common. Prevalence of 0.6/1000 but the disease is clinically symptomatic in less than 10% of patients with the mutated gene, rarely in childhood, most frequently in the young, usually female (80 % of cases) adult.

The orphyrias are classified in 2 groups according to the type of risks incurred by the patients when exposed to an triggering agent:

- hepatic porphyrias expose to a vital risk, including during anesthesia, by the outbreak of a so-called acute crisis, the "acute porphyric crisis"

- cutaneous porphyrias the potential anesthetic risk is potentially is cutaneous but never vital.

Special forms:

(1) erythropoietic congenital porphyria (Gunther disease)

Very rare, autosomal recessive transmission of a deficiency in uroporphyrinogen III cosynthetase. The accumulation of porphyrins in many tissues causes photosensitization, hirsutism and severe skin lesions (bullous lesions, open surinfected wounds and sores) from early childhood. Treatment involves frequent dressings under anesthesia, iterative blood transfusions, occasionally splenectomy. The severity of the condition often justifies a bone marrow transplant.

(2) ALAD porphyria and acute intermittent porphyria

These two conditions are clinically similar but differ by the causal defective enzyme, their mode of transmission (dominant for acute intermittent porphyria) and their frequency, acute intermittent porphyria being, by far, the most frequent.

The disease can remain asymptomatic throughout life. When it is clinically expressed, it starts most commonly after puberty and the symptoms are non specific: nausea, vomiting, constipation, vague back and limbs pain, muscle weakness, retention of urine, palpitation, episodes of confusion and hallucinations, sometimes seizures. Occasionally hyponatremia contributes to the symptomatology. The diagnosis is made on the basis of the increase of acid δ-aminolevullinic and porphobilinogen in urine, the absence of porphobilinogen deaminase (fickle) in erythrocytes and in molecular biology.

Acute intermittent porphyria exposes the patient to frequent bouts of acute severe decompensations ("acute porphyric attack"), including or following anesthesia.

(3) porphyria cutanea tarda

This hepatic porphyria is rarely genetically transmitted (autosomal dominant transmission of a mutation of the UROD gene), but is usually acquired as a result of liver disease caused by exposure to toxics (alcohol, estrogens, oral contraceptives) or infectious agents (hepatitis C, HIV). Its clinical expression is basically cutaneous (cutaneous blisters or erosions with permanent scar) and affects only exceptionally the pediatric age group (in this case, there is often a favoring factor inducing an iron overload or oxidative stress, such as the mutation of another gene). His treatment is relatively easy (iterative phlebotomies) to reduce serum iron levelsand the risk of hepatic hemochromatosis. Chloroquine derivatives are sometimes used.

(4) hepato-erythropoietic porphyria

Rare form of porphyria, of autosomal recessive transmission; results of the same enzyme deficiency as porphyria cutanea tarda. Clinically, it looks like a congenital erythropoietic porphyria with early injuries starting in early childhood.

(5) hereditary coproporphyria

Hepatic porphyria transmitted as autosomal dominant disease. The clinical presentation is quite similar to acute intermittent porphyria with the same risk of acute porphyric attacks (with the same treatment).

(6) porphyria variegata

Autosomal dominant form which affects mainly subjects of white South African ancestry (incidence 1/300 in the Afrikaner population). Patients are also exposed to the risk of acute porphyric attack.

(7) Porphyria Erythropoietic

Prevalence: 1/78.000 to 1/200.000. Ferrocholatase deficiency (mutation of the FECH gene) is transmitted as an autosomal dominant trait. Another rarer form is linked to a mutation (leading to an increased function) of the ALAS2 gene (chromosome X) leading to the overproduction of protopophyrin. The clinical symptoms appears after sun exposure (even behind glasses): skin lesions with bubbles, bedsores and later areas of discoloration. Disease usually manifest itself during childhood. Anemia is present in 40 % of patients and anomalies of the liver enzymes are present in 25 % of cases leading to a risk of early biliary lithiasis and biliary cirrhosis.Treatment with ß-carotene improves tolerance to sun exposure but has no effects on the level of porphyrin (cholestyramine may lower these levels in some patients). There are trials of treatment with afamelanotide, a synthetic analog of the hormone stimulating the α-melanocytes, and with dersimelagon, a selective agonist of the melacortine 1 receptors.

Porphyria, acute crisis :

occurs typically in a young woman, often triggered by:

- intake of drugs (barbiturates, sulphonamides, oestro-progestogestatives...) ,

- excessive intake of alcohol or illicit drug use,

- hypocaloric diet,

- infection

- the menstrual cycle and hormonal treatments.

Symptoms combine variable abdominal pain, sometimes psychiatric and neurologic signs. Abdominal pain usually appears first and combines continuous or paraxysmal severe pain, continuous or paroxysmal, with no predominant location but radiating to the lower limbs; it is accompanied by nausea and vomiting that can lead to important hydroelectrolytic disorders. The clinical and radiological abdomen examination (ultrasound) reveals no objective cause. Tachycardia usually without fever, and episodes of high blood pressure and sweating that reveal impairment of the autonomic nervous system are frequently described.

The neurological signs and symptoms are multiple and can affect the peripheral and central nervous system. They are: simple paresthesia, myalgia, paresis, peripheral or central disorders (rare) coma or convulsions (frequent) the treatment of which by barbiturates ( porphyrinogenic molecules by excellence) can aggravate the clinical picture. These events may be fatal (bulbar impairment, respiratory paralysis). These neurological impairments are rarely inaugural and are most often triggered or exacerbated by inappropriate treatment, administered in the absence of diagnosis.

In this context, the observation of abnormal discoloration of urine in a reddish-brown "porto wine" color should evoke the diagnosis. But this major component may be missing as the discoloration appears only 30 to 60 minutes after urination.

Treatment of the crisis :

analgesics, antiemetics and increased carbohydrate intake to control the metabolic crisis. The most effective treatment is, however, intravenous administration of heme as early as possible after the beginning of the crisis: heme arginate 3-4 mg / kg by day in 20 minutes and for 4 successive days

Anesthetic implications:

Avoid medications that can trigger an acute crisis (see table). Their list is constantly evolving: specialized websites:

- American Porphyria Foundation : http://www.porphyriafoundation.com

- European Porphyria Initiative : http://www.porphyria-europe.com

- South-African Porphyrias center : http://webdav.uct.ac.za/depts/porphyria

- French center for Porphyrias (AP-HP : Hôpital Louis Mourier – UFR X BICHAT - 92701 Colombes Cedex. Tel: (1) 47.60.63.34 ou 47.60.63.35. Fax (1).47.60.67.03) http://perso.wanadoo.fr/porphyries-france/

- www.drugs-porphyria.org

Shorten the perioperative fasting period, reduce stress and avoid precipitating agents. Sevoflurane is a good choice for induction of anesthesia. Propofol can be used but avoid intravenous total anesthesia. The amide local anesthetics are no longer considered as a porphyrinogenic.

In case of congenital erythropoietic porphyria (Gunther disease), exposure to visible light should be limited, especially in the operating room (sources of light covered with a yellow acrylate filter, protection of the skin outside the operating field with a sheet). Scarring on the face can cause perioral sclerosis, limit of the extension of the neck and a nasal necrosis leading to difficult intubation.

|

Aminoglutethimide |

Ergot

|

Orphenadrine |

|

Barbiturates |

Erythromycin |

Oxcarbazepine |

|

Carbamazepine |

Etamsylate |

Oxtriphyl |

|

Chloramphenicol |

Ethosuximide |

Phenylbutazone |

|

Clemastine |

Etomidate |

Phenytoin |

|

Clonidine |

Griseofulvin |

Primidone |

|

Co-trimoxazole |

Systemic ketoconazole |

Estro progestogens |

|

Danazol |

Meprobamate |

Pyrazinamide |

|

Dapsone |

Mesuximide |

Pyrazolone |

|

Dihydralazine |

Methyldopa |

Sulphonamides |

|

Dimenhydrinate |

Methysergide |

Tolbutamide |

|

Regina |

Nalidixic acid) |

|

List of drugs prohibited in case of Porphyria

References :

- Hultdin J, Schmauch A, Wikberg A, Dahlquist G, Andersson C.

Acute intermittent porphyria in childhood: a population-based study.

Acta Paediatr 2003;92:562-8.

- Sheppard L, Dorman T.

Anesthesia in a child with homozygous porphobilinogen deaminase deficiency: a severe form of acute intermittent porphyria.

Pediatr Anesth 2005;15:426-8.

- Anderson KE, Bloomer JR, Bonkovsky HL, Kushner JP, Pierach CA, Pimstone NR, Desnick RJ.

Recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of the acute porphyrias.

Ann Intern Med 2005;142:439-50.

- Harris C, Hartsilver E.

Anaesthetic management of an obstetric patient with variegate porphyria.

Int J Obstet Anesth 2013; 22: 156- 60.

- Nagarajappa A, Kaur M, Sinha R. Anesthetic concerns in the patients with congenital erythropoietic porphyria for ocular surgery. J Clin Anesth 2019; 54: 3-5

- Lala SM, Naik H, Balwani M.

Diagnostic delay in erythropoietic protoporphyria.

J Pediatr 2018 ; 202: 320-3

- Kuemmet TJ, Sokumbi O, Chiu YE.

New-onset blistering eruption in a young child.

J Pediatr 2019; 205: 290-1

Updated: April 2023