Dyskinesia of the larynx resulting in a more or less complete collapse of the supraglottic structures during inspiration and producing a stridor. Frequently associated with prematurity, laryngomalacia is the most frequent (60 %) congenital disorders of the larynx and the most common cause of congenital stridor. Its possible and often associated causes are:

- abnormal development of the epiglottic cartilaginous structures : it is physiologically longer and has frequently a tubular appearance or 'omega' shape, which facilitates its posterior prolapse.

- short aryepiglottic folds that prolapse into the glottic apperture during inspiration

- gastroesophageal reflux: stridor appears only after several days of life and signs of inflammatory injury of the laryngeal mucosa, are constantly found;

- a delay in maturation of the neuromuscular control of supra-glottic structures leading to an inspiratory prolapse of the arytenoids; some diseases accompanied by hypotonia (such as trisomy 21 or the CHARGE syndrome) can cause pharyngo-laryngomalacia.

Clinical presentation: in the classical form, the neonate presents with intermittent inspiratory whistling during the first two weeks of life; it worsens progressively during the first 4 to 6 months of life and then improves gradually later over a period of about 2 years as the laryngeal growth is faster than that of the supraglottic structures. Stridor [from the latin "stridor", is an high-pitched inspiratory permanent or intermittent whistling, accompanying inspiratory movements of the chest and caused by an incomplete obstruction of the larynx or trachea] increases in the supine position, during feedings and periods of agitation, and decreases when the neck is hyperextended or in the prone position. The phonation and cry are normal.

However stridor may be symptomatic of a laryngeal or tracheal anomaly causing the development of secondary laryngo-tracheo-bronchomalacia: subglottic stenosis, subglottic hemangioma, congenital vocal cords paralysis, congenital vascular anomaly, laryngeal cyst or subglottic cyst or sequelae of laryngotracheal surgery (esophageal atresia).

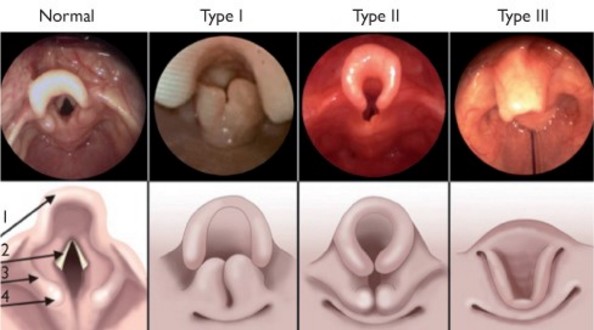

Dynamic examination with awake nasal fibroscopy or during direct laryngoscopy in the anesthetized child (maintaining spontaneous ventilation) allows to observe the laryngeal structures, determine the mechanism of the laryngomalacia and exclude the presence of other causes of stridor.

P. Monnier classification (Pediatric airway surgery: Management of laryngotracheal stenosis in infants and children. 2010):

- type 1: inward prolapse of the aryepiglottic folds at inspiration

- type 2: tubular epiglottis and short aryepiglottic folds that prolapse circumferentially during inspiration

- type 3: epiglottis prolapsing after the inspiration

Treatment:

- in the majority of cases, management is essentially a wait-and-see strategy, monitoring the development and growth of the child, dealing with gastroesophageal reflux disease and feeding difficulties.

- in 15 to 20 % of cases, severe respiratory distress episodes of cyanosis with establishment of an clinical situation of chronic cor pulmonale or important feeding difficulties lead to consider, depending on the type of laryngomalacia, a plasty of the epiglottis or a division of the ary-epiglottic folds. These interventions by microsurgery, typically made using a CO2 laser are performed under laryngoscopy under suspension laryngoscopy.

- however, the development of major respiratory difficulties may lead to perform a tracheotomy during an acute crisis.

Anesthetic implications:

increased risk of upper airway obstruction during at the induction and awakening from anesthesia; in case of intubation, it is wise to start with a tracheal tube with a smaller diameter than expected for the child’s age. In case of ENT examination under general anesthesia, it should be borne in mind that topical anaesthesia of the glottis can exaggerate the signs of laryngomalacia: it is mandatory to coordinate with the ENT surgeon before any such examination. One might, for example, wait to spray the glottic structures with lidocaine until after an initial inspection of the glottis by the ENT surgeon.

References :

- Boudewyns A, Claes J, Van de Heyning P.

Clinical practice: an approach to stridor in infants and children.

Eur J Pediatr 2010; 169:135-41.

- Ayari S, Aubertin G, Girschig H, Van Den Abbeele T, Mondain M.

Pathophysiology and diagnostic approach to laryngomalacia in infants.

Eur Annals of Otorhinolaryng, Head and Neck Dis 2012; 129: 257-63.

- Ahmad SM, Soliman AM.

Congenital anomalies of the larynx.

Otolaryngol Clin North Am 2007; 40:177-91.

- Lee KS, Chen BN, Yang CC, Chen YC.

CO2 laser supraglottoplasty for severe laryngomalacia: a study of symptomatic improvement.

Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2007; 71:889-95.

- Richter GT, Thompson DM.

The surgical management of laryngomalacia.

Otolaryngol Clin North Am 2008; 41:837-64.

- Nielson DW, KU PL, Egger M.

Topical lidocaine exagerates laryngomalacia during flexible bronchoscopy.

Am J Respi Crit Care Med 2000; 161:147-51.

Updated: February 2019