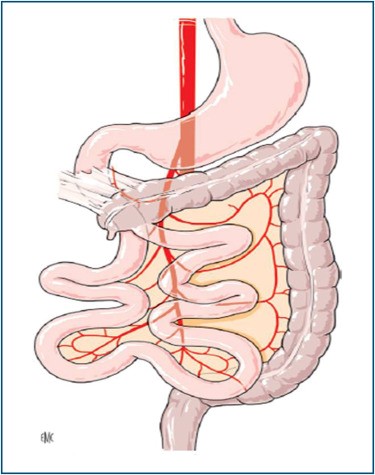

Fibrous stalk of peritoneal tissue attaching the cecum to the right posterior abdominal wall. In case of intestinal malroration, it crosses the 2nd duodenum anteriorly, compressing it or causing a volvulus.

Intestinal malrotation is the most common congenital anomaly of the small bowell. It is estimated that its prevalence is around 1 in 200 live births. However, it becomes symptomatic in about 1 in 6000 live births.

Pathophysiology of intestinal malrotation: during embryonic development, the primitive intestinal loop herniates out of the abdominal cavity. When it gets back into the abdomen, the intestine normally undergoes three successive counterclockwise rotations of 90° each, centered on the superior mesenteric artery. In case of complete rotations, the cecum finally ends in the right iliac fossa where it creates adhesions to the retroperitoneum. If the rotation is incomplete or abnormal, the cecum is located elsewhere (usually in the right hypochondrium or the epigastrium), and adhesions with the local retroperitoneum develop.

There are 2 types of anomalies:

- complete common mesentery: rotation has stopped after the first 90° rotation: the colon remains on the left and the small intestine is arranged right to the midline. The cecum is in an anterior median position with the appendix on its right side. The duodenum does not pass between the aorta and the superior mesenteric artery. There is no risk of midgut volvulus as the mesenteric base is long. It is asymptomatic. Often associated with a diaphragmatic hernia.

- incomplete common mesentery: stop after two rotations of 90 ° (overall rotation of 180 °): risk of midgut volvulus as the mesenteric base is short

Ladd's band compressing the duodenum

Anesthetic implications:

management of a subacute (Ladd's band) or acute (in case of volvulus) intestinal occlusion.

In case of volvulus, acute hemodynamic instability may occur at the time of its derotation because lactic acid and other vasoactive compounds are released in the blood. Brisk acidosis and hyperkalemia are not uncommon and should be managed with IV calcium and fluid loading.

References:

Updated: February 2019