Rare: 1/25,000 to 1/30,000 births. Chondrodysplasia is of sporadic origin in 90 % of cases (in relation with the father's age) but autosomal dominant transmission is present in the remaining 10 %. It is caused by a gain-of-function mutation of the FGFR3 gene (4p16.3) coding for a fibroblast growth factor receptor expressed in growth cartilage.

Clinical presentation:

- disproportionate dwarfism with:

1) large head size (macrocephalia with large ventricles, sometimes hydrocephaly: a ventriculo-peritoneal shunt is necessary in 3-5 % of cases) with frontal bossing and midface hypoplasia; delayed closure of the cranial sutures (anterior fontanel open until 5-6 years of age)

2) short stature: mean adult height: 124 cm for women and 132 cm for men

3) short and narrow chest

4) short limbs: rhizomelic shortening

- stenosis of the jugular foramen which can impair the cerebral venous return and contribute to hydrocephaly

- stenosis of the foramen magnum occipitalis (45 %) (white arrow on the IRM below) that can produce hypertonia or hypotonia, hydrocephaly (17 %) and spinal cord compression (17 %) and an increased risk of sudden death before 2 years of age (2 to 3 %; causes: apneas and /or compression of the vertebral arteries during sleep); decompressive surgery at the cervico-occipital level can be indicated during the first two years of life; instability of the atlanto-axial joint is rare

.jpg)

- breathing problems during sleep due to the association in various proportions of:

* obstructive apnea (69 %) causd by the presence of tonsils and adenoids of normal size in a narrow pharyngeal cavity

* central apneas (16 %)

* decreased tonus of the pharyngeal dilator muscles due to hydrocephalus (stenosis of the jugular foramen )

* decreased tonus of the pharyngeal dilator muscles in the absence of hydrocephalus but due to a stenosis of the hypoglossal canal, with or without compression of the foramen magnum occipitalis

* gastroesophageal reflux

- restrictive syndrome (small very compliant chest: frequent paradoxical breathing in the infant) with risk of chronic cor pulmonale if sleep apneas are not corrected

- cyphosis in childhood (83 %) that disappears after treatment with a brace

- lumbar hyperlordosis with a risk of narrow spinal canal (43 %) and spinal claudication (paresthesias during exercice disappearing at rest) but also neurologic bladder, paraparesia or paraplegia). In case of neurologic signs, decompressive surgery is required in 33 % of cases,

- deformation of the ribs, sometimes scoliosis;

- genu varum, subluxation of the radial head with limitation of extension of the elbows

- short fingers and trident hands (significant space between the 3rd and 4th finger)

- hearing problems

- normal intelligence.

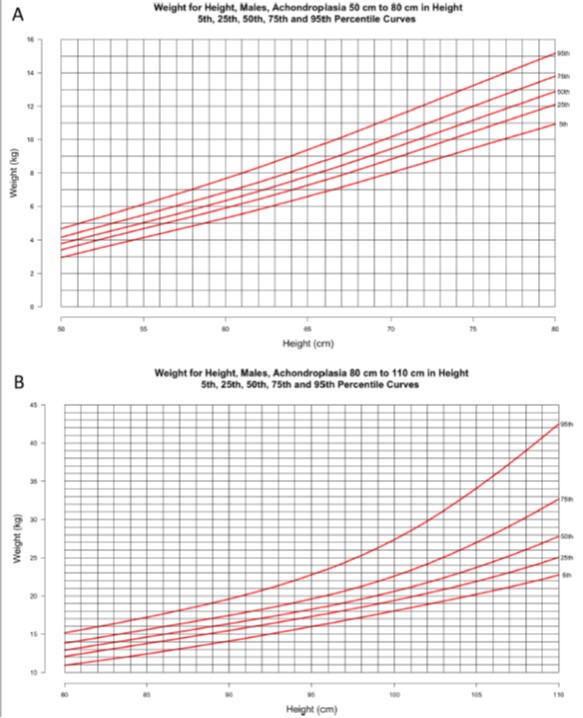

Population height-weight chart for achondroplastic boys (a) and girls (b)

(Orphanet J Rare Diseases, 2021; 16:522)

Main problems according to age:

- < 2 years :

- obstructive sleep disorders (> 50 %)

- chronic upper airway obstruction and hearing impairment

- foramen magnum stenosis: sometimes brain stem compression and sudden death

- thoracolumbar kyphosis

- 3-5 years :

- obstructive sleep apnea

- genu varum

- sometimes recurrence of foramen magnum stenosis

- 6-18 years

- symptomatic spinal stenosis (10-20 %)

- obstructive sleep apnea

- genu varum

- chronic pain (back, lower limbs)

Treatments:

- in phase 3: Vosoritide (CNP (C-type natriuretic peptide) analogue) 15 µg/kg subcutaneously every day.

- phase 1 or 2:

* navepegritide: CNP (C-type natriuretic peptide) analog: weekly subcutaneous injection

* infigratinib: selective FGFR1-3 inhibitor, p os

* meclizine: antihistamine, os

* SAR-442501: monoclonal antibody against FGFR3

* RBM-007: FGFR3 receptor blocker for fibroblasts

These treatments increase bone growth, but their long-term effects and potential drug interactions are still unknown.

Anesthetic implications:

difficult manual ventilation by mask and a difficult intubation should be anticipated (relatively large head, short neck, large tongue, limited extension of the neck), choanal narrowing, sleep apnea, restrictive syndrome, risk of spinal cord compression at the level of the cranio-cervical junction, narrow foramen magnum (careful positioning of the head). Endotracheal tube diameter: choose size according to weight rather than age; significant risk of bronchial intubation.

Avoid any brisk movements of the head, either in flexion or extension (use neck pillow as for airflights) during transfer or positioning; avoid using swing for infants.

Neuraxial block can be difficult to perform: lumbar hyperlordosis, sometimes scoliosis; narrow lumbar canal: less CSF volume associated with an increased risk of neurological sequelae after a neuraxial block. Peripheral nerve blocks: feasible if echoguided.

|

EXPERT CONSENSUS for MANAGEMENT:

Surgical morbi-mortality is higher than in the normal population and the risk of anesthetic complications is very high: these patients must therefore be managed in facilities where care of those complications can be undertaken. It is why : - a full neurological examination is necessary before general or locoregional anesthesia - full spine imaging (MRI or CTscan) is recommended - a flexion/extension MRI of the cervical spine is necessary if there is any concern about its stability - polysomnography, respiratory functional tests (restrictive or obstructive syndrome) and cardiac evaluation (echocardiography) must be considered before anesthesia - morphological and functional anomalies of the upper airway, a decrease in mobility of the cervical spine and bronchial airway anomalies increase the morbidity and mortality of anesthesia - a sedative premedication can be administered before anesthesia - for intubation, a videolaryngoscope and a intubating fiberscope must be immediately available - tracheostomy can be extremely difficult in those patients, particularly in emergency; it is crucial to identify the position of the cricothyroid membrane (XRays, echography) before anesthesia - extubation should be preferably performed in the operating room; if this cannot be the case, an experienced team must be present - in patients in whom fragility of the spinal cord is suspected (concept of spinal cord at risk : significant cyphosis, risk of hypotension, long lasting surgery, difficult surgical positioning), neurological monitoring must be undertaken during the whole procedure, and it is better to avoid epidural anesthesia Reference:

|

References :

- Mayhew JF, Katz J, Milner M Leiman BC, Hall ID.

Anesthesia for the achondroplastic dwarf.

Can J Anaesth Soc J 1986: 33: 216-21

- Monedero P, Garcia-Pedrajas F, Coca I et al.

Is management of anaesthesia in achondroplastic dwarfs really a challenge?

J Clin Anesth 1997; 9: 208-12.

- Berkowitz ID, Raja SN, Bender KS, Kopits SE.

Dwarfs: pathophysiology and anesthetic implications.

Anesthesiology 1990; 73:739-9.

- Sisk EA, Heatley DG, Borowski BJ, Leverson GE, Pauli RM.

Obstructive sleep apnea in children with achondroplasia: surgical and anesthetic considerations.

Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1999; 120:248-54.

- Dubiel L, Scott GA, Agaram R, McGrady E, Duncan A, Lichtfield KN.

Achondroplasia: anaesthetic challenges for caesarean section.

Int J Obstetr Anesth 2014; 23: 274-8.

- Van Hecke D, De Villé A, Vann der Linden P, Faraoni D.

Anaesthesia and orphan disease: a 26-year-old patient with achondroplasia.

Eur J Anaesthesiol 2013; 30776-80

- Eiszner JR, ATanda A Jr, Rangavaljjula A, Theroux M.

A case series of peripheral nerve blocks in pediatrics and young adults with skeletal dysplasia.

Pediatr Anesth 2016 ; 26 :553-6.

- Ockenfuss E, Moghaddam B, Avins AL.

Natural history of achondroplasia: a retrospective review of longitudinal clinical data.

Am J Med Genet 2020; 182A: 2540-51.

- Hoover‑Fong JE , Schulze KJ, Alade AY, Bober MB, Gough E, Hashmi SS, Hecht JT, Legare JM, Little ME et al.

Growth in achondroplasia including stature, weight, weight‑for‑height and head circumference from CLARITY: achondroplasia natural history study-a multi‑center retrospective cohort study of achondroplasia in the US.

Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 2021 ; 16:522 doi.org/10.1186/s13023-021-02141-4

- Savarirayan R, Ireland P, Irving M, et al.

International Consensus Statement on the diagnosis, multidisciplinary management and lifelong care of individuals with achondroplasia.

Nat Rev Endocrinol 2022; 18: 173–89.

- Savarirayan R, Hoover-Fong J, Yap P, Fredwall. SO.

New treatments for children with achondroplasia.

Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2024; 8: 301–10

Updated May 2024