Estimated prevalence: 9 to 10/100.000. Progressive disappearance of the nerve cells of the myenteric plexus: the cause can be infectious (e.g.,Chagas disease) or autoimmune. Signs and symptoms: dysphagia appearing sometimes late (adolescence, adulthood) resulting in failure to thrive, late "vomiting" in infancy, frequent pneumonia, asthma refractory to treatment (as a result of repeated infections and/or tracheobronchial compression by the dilated esophagus) and bronchiectasis; sometimes retrosternal pain.

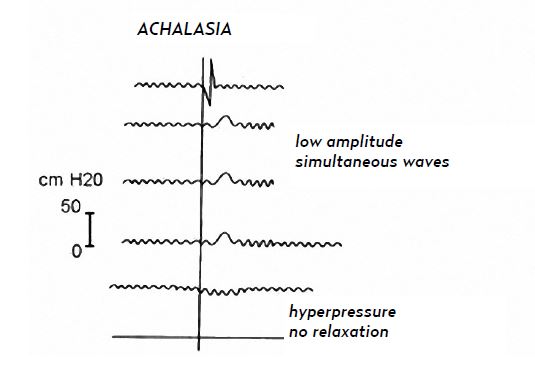

High resolution manometry allows to distinguish 3 types of achalasia by measuring the integrated relaxation pressure (median lowest measured pressure for 4 seconds during the 10 seconds following the relaxation of the superior esophageal sphincter) and the esophageal contractility (classification of Chicago):

- type I or classic form: high integrated relaxation pressure, no peristalsis, no esophageal contraction.

- type II: high integrated relaxation pressure, no peristalsis, pressurisation of the whole esophagus concerning more than 20% of the swallowings

- type III: high integrated relaxation pressure, no peristalsis, premature and localized esophageal spasms in more than 20% of the swallowings.

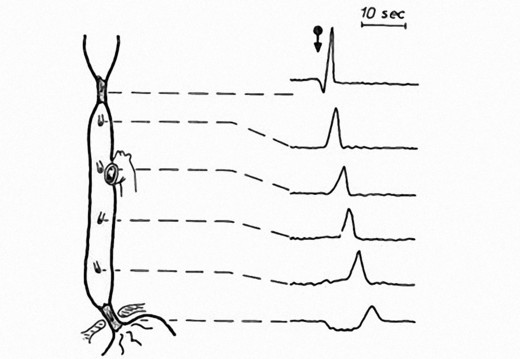

normal esophageal manometry

Treatment: according to the type of achalasia, nifedipine before meals, esophageal dilatations, botulinic toxin injections in the lower esophageal sphincter, Heller myotomy associated with a partial anti-reflux surgery (either open or laparoscopic Toupet procedure) or submucosal myotomy by the oral route (endoscopic).

Anesthetic implications:

frequent respiratory infections. Management for a 'full esophagus' situation: the dilated esophagus should be emptied with a large bore gastric tube before induction of anesthesia: cricoid pressure is useless and potentially dangerous in this context.

The cure by endoscopy necessitates an incision of the esophageal mucosa followed by submucosal insufflation of CO2 to create a submucosal tunnel and allow the myotomy of the circular muscular fibers at the level of the gastroeosophageal junction.

In adults, this technique results in significant CO2 resorption with a significant risk of cervical and mediastinal emphysema (28%) as well as a capnoperitoneum that may require needle decompression to facilitate ventilation (32 %). In adults, intraoperative administration of MgSO4 (50 mg/kg then 25 mg/kg/h) significantly reduces postoperative spasm and pain.

References :

- François N, Chouraqui M, Babre F, Maurette P, Nouette-Gaulain K.

Fibroscopie oeso-gastro-duodénale diagnostique chez l’adolescent : quand penser à l’achalasie du cardia ?

Ann Fr Anesth Réanim 2012 ; 31 : 72-5.

- Li Y, Fallon SC, Helmrath MA, Gilger M, Brandt ML.

Surgical treatment of infantile achalasia : a case report and literature review.

Pediatr Surg Int 2014 ; 30 : 677-9.

- Ekstrom BG, Dance S, Low DE, Fagley RE.

Successful airway management in a patient with severe proximal achalasia requires interdisciplinary cooperation.

A & A Case Reports; 2014; 3: 153-5.

- Nabi Z, Ramchandani M, Reddy DN, Darisetty S et al.

Per oral endoscopic myotomy in children with achalasia cardia.

J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2016; 322: 613-9.

- Löser B, Werner YB, Punke MA, Saugel B, Haas S, Reuter DA et al.

Anesthetic considerations for patients with esophagral achalasia undergoing peroral endoscopic myotomy : a retrospective case series review.

Can J Anesth 2017 ; 64 : 480-8.

- Kim RK, Kim J, Angelotti T, Esquivel M, Tsui BC, Hwang JH.

Magnesium and esophageal pain after peroral endoscopic myotomy of the esophagus: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial.

Anesth Analg 2025; 140 :54-61

Updated: December 2024